Selecting a Knife for Bushcraft and Wilderness Use

by Zig Zag, Warrior Publications, September 18, 2014

“The knife is the smallest and most portable of all the cutting tools. Light and unobtrusive, the knife is readily available for hundreds of everyday tasks in bush living.”

(Mors Kochanski, Bushcraft, p. 109)

A knife is one of the most important tools for use in a wilderness area, whether for bushcraft or survival. It can be used to cut and carve wood for shelters, stakes, traps, hooks, spears, walking sticks, etc. It can be a vital tool when making a fire, from cutting and splitting wood to making friction fire drills, feather sticks, etc. A knife is used to clean, skin, and butcher animals or fish, to cut rope or cordage, etc. A knife can also be used as a weapon for self-defence.

Along with the hammer and axe, the knife was one of the first tools used by early humans. Prehistoric knives were made of rock (such as flint or obsidian), bone, shell, or wood. When people began practising metallurgy, knives began to be made of copper, then iron and steel.

In selecting a knife, consider the environment you are in and the potential uses of the knife. These factors will determine the type of knife that will be best suited for your purposes. This article focuses on general purpose knives that are suitable for wilderness or bushcraft use, primarily wood and food processing.

Ideally, we would need only one tool for all our cutting purposes. It would be able to chop down small trees, process these into smaller lengths, split them, and then at the end of the day carve a nice little spoon. Some people look for the ultimate wilderness or survival knife that can accomplish all these tasks (others just look for the biggest, baddest-looking knife they can find). But at the end of the day, they usually end up with a large knife that is still too small to chop down small trees, yet too big to do any fine carving. Instead, it is best to get an axe (or tomahawk) to use for larger chopping work, a small folding saw for quickly cutting smaller pieces of wood, and a medium sized knife for finer wood carving, food processing, and general utility work. This way, you have a good tool for chopping while preserving your knife for work it is better suited for.

Knife and sheath which had reportedly belonged to Crazy Horse, a trade knife. Total Length of 9.5″ Long, Blade Length 5″ Long, Beaded Sheath Measures 7.5″ Long.

Knife Types

Today there are a wide variety of types of knives for many different purposes, such as filet knives for cleaning fish, hunter’s knives designed for skinning an animal, general utility knives, carving knives for wood working, diver’s knives, etc.

For general wilderness use, there are some knife types that are better suited than others, and some that are simply impractical. Most general purpose utility knives are good for bushcrafting in that they have a 4-5 inch blade that is straight and curves upward towards the tip. The handle length is also about 4-5 inches in length, which makes for a well balanced knife that can be easily held in the hand, in various grips, and be used for carving.

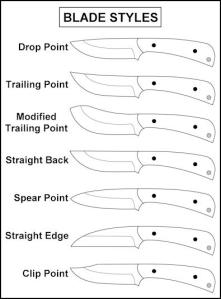

A good utility or hunting knife with either a drop point, spear point, clip point, straight back, or trailing point blade design is more suitable for bushcraft as these can be used to drill holes (such as for a friction fire board). They can also still be used for stabbing if necessary. In addition, these types of blade designs also allow for better overall wood cutting as they have a straight portion (near the handle) which is good for planing or splitting, and a continuously curving edge towards the tip, which enables more precise and controlled carving.

A good utility or hunting knife with either a drop point, spear point, clip point, straight back, or trailing point blade design is more suitable for bushcraft as these can be used to drill holes (such as for a friction fire board). They can also still be used for stabbing if necessary. In addition, these types of blade designs also allow for better overall wood cutting as they have a straight portion (near the handle) which is good for planing or splitting, and a continuously curving edge towards the tip, which enables more precise and controlled carving.

A few knives have saw teeth on the spine of the knife, and while this is useful it limits the use of the spine for carving and batoning. The older US Air Force survival knife has saw teeth on the back, but they are designed to cut through aluminum and enable pilots to escape from their aircraft during a crash. It can cut wood but not as effectively as a small folding saw.

Knives that have serrations are not that useful for bushcrafting, as the serrated edges will leave uneven cuts, which is not ideal when trying to carve a smooth finish. Serrations also require special sharpeners that are rounded. Serrated edges are primarily designed to cut nylon rope and webbing.

A knife with a double edged blade, such as a dagger, is not good for general field use or bushcrafting as you cannot place your hand or thumb on the back of the blade while carving, nor can you baton with it as the sharp upper edge will chew your baton up. A dagger has only one main purpose and that is for stabbing.

Large knives with blades 8-12 inches long, while being good at chopping, are too large for fine carving (as well as many other tasks that require more precise cutting). Because they are large and heavy, you are also less likely to carry it on a daily basis.

Fantasy-style knives, with deep curving blades and dragons heads for handles, are also not very practical for bushcrafting as they tend to be heavy and the handles severely limit the types of grips one can use.

Cheap “Rambo” style survival knives with hollow handles should be avoided due to their poor (or non-existent) tang construction. There are high quality hollow handle survival knives made from one piece of steel, but these are expensive and in cold weather the handle also becomes cold.

Of course, in a wilderness survival situation, any type of knife or edged tool is useful. And throughout the 1700s and 1800s, most people used butcher knives as their main field knife (referred to as “trade knives,” Native peoples frequently rehandled these and made leather sheaths to carry them in). But today, with a wide variety of knife types to choose from, it makes sense to get a knife that best suits your needs.

Knife Grind

There are different types of knife grinds, which is the way the blade’s cutting edge is designed. The knife grind also affects the cutting ability of the knife. Some knife grinds are better suited for certain tasks than others, and some are easier to sharpen than others.

There are four grind types that are most commonly found on knives: convex, sabre, scandi, and hollow grind. As with many ancient arts, there are multiple terms used to describe grind types and ongoing debate over precise definitions.

Convex Grind: A convex grind consists of a continually rounding blade that terminates in a sharp point. The convex grind is more common on axes, tomahawks, and kukris, as it very good for splitting and chopping wood, but is also found on some bushcrafting and survival knives (such as some of the Fallkniven knives). This grind puts more metal behind the edge, resulting in a stronger blade edge.

A convex grind can be more difficult to sharpen, and many people resort to using a mouse pad and sandpaper to retain the convex profile (which can otherwise be ground down to a partial flat grind on a hard stone). An alternate method of sharpening is to use a small stone in a circular pattern along the edge of the blade (as one might also sharpen an axe).

Sabre Grind: Also known as a compound or secondary bevel grind, as well as a flat grind with a secondary bevel. The sabre grind consists of a main bevel, or angle, and a smaller secondary one that is the actual blade edge. It is very common today among mass produced knives as it is among the easiest to manufacture. When sharpening a sabre grind, the knife must be held at the same angle as the blade edge and pushed across the sharpening stone. Some people have a hard time finding the correct angle and as a result are unable to sharpen their knife to a high degree.

Scandi Grind: For wood working, one of the best grinds is a Scandi grind, so called for its widespread use in the Scandinavian countries (a result of the influence of the Indigenous Sami people). Most Mora knives, as well as many bushcrafting knives, have a Scandi grind. This grind is also the easiest to sharpen, as it consists of just one angle (or bevel) that is laid flat on a sharpening stone and pushed across it.

Hollow Grind: Not as common as the other grinds, a hollow grind consists of a hollowed out (concave) upper portion on the blade, narrowing down to a secondary bevel that is the knife edge. Hollow grinds have less metal behind the cutting edge and are therefore lighter, as well as thinner and weaker. They are sharpened in the same manner as a sabre grind.

Knife Tang

The tang is the steel portion that extends past the point where the handle meets the blade. The handle is secured to the tang, usually with pins, screws, bolts, or glue/epoxy. The length and type of tang determines the overall durability of the knife (along with heat treatment and type of steel used). Cheap kitchen knives often have just a small tang that is glued or bolted into the handle. While this is good enough for cutting potatoes and onions, this type of construction is not strong enough for field use. Many of the cheap “Rambo” style knives, with the hollow handle, have no tang at all, they are just glued or soldered on. As a result, these types of knives are easily broken.

There are five main types of tangs used in field knives: full, skeletonized, partial, narrowing, and the stick or rat tail tang. Like knife grinds, there is ongoing debate over precise definitions of tangs, but these are among the most commonly used terms.

Full Tang: Some people prefer full tang knives, in which the tang is the same width as the blade and extends all the way through the handle, which is usually comprised of two scales (the handle slabs) bolted and/or glued to the tang. When you look at the handle of a full tang knife, you will see the metal tang running between the two sides of the handle. This type of construction is the most durable, although it also adds some weight to the knife (as well as cost).

Full Tang: Some people prefer full tang knives, in which the tang is the same width as the blade and extends all the way through the handle, which is usually comprised of two scales (the handle slabs) bolted and/or glued to the tang. When you look at the handle of a full tang knife, you will see the metal tang running between the two sides of the handle. This type of construction is the most durable, although it also adds some weight to the knife (as well as cost).

A full tang knife is preferred by those who envision one day having only one knife for survival, and which must be strong enough for batoning wood (either for splitting wood for fire making or for cutting down saplings for shelter). Despite this, full tang knives can be broken, either in the tang or the blade, most often by batoning, prying, or throwing.

Skeletonized Tang: This type of tang may appear as a full tang, but under the handle it is skeletonized with portions cut out of it. This makes the knife lighter while still retaining a great deal of strength. Some survival or utility knives come with a skeletonized tang around which paracord is wrapped to form the handle as well as emergency cordage.

Partial Tang: While a full tang knife is stronger than a partial or narrow tang, some of the most popular knives for bushcraft are produced by Mora, a Swedish knife making company. Almost all their knives have a partial tang inserted into a plastic or rubberized handle. Although they will break if a lot of pressure is exerted (usually from batoning), Mora knives are durable enough for almost all bushcraft work (including light batoning of small pieces of wood), and the least expensive. A light weight, partial tang knife is often paired with a small axe, tomahawk, or a larger and heavier knife for chopping and splitting larger pieces of wood.

Narrowing Tang: Also known as a tapering tang. This tang usually extends from the blade to the end of the handle, becoming increasingly narrow. Similar to a rat tail tang but starts wider and then narrows down, often wider than a rat tail tang (as used in traditional Leuko knives used by Sami people and people in northern Scandinavia).

Stick Tang / Rat Tail: As the name suggests, the stick tang is a thinner portion of steel that extends from the blade to the butt of the handle, often being pinned or bolted in place. Although not as strong as a full tang, the stick tang was the most common type of knife tang until the late 20th century and is still durable enough for bushcraft type knives.

The stick tang is still used in the Ka-bar line of fighting-utility knives, first designed for US soldiers during WW2. Traditionally made kukris, such as those made today in Nepal, also use a stick tang. The classic Mora’s Number 1 and 2 have stick tangs running through a birch handle that is usually painted red. These knives were among the most commonly found utility knives in the 1970s, and are still available today.

Some refer to a stick tang that extends the length of the handle as a full tang, as well as a hidden tang.

Blade Steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon. The amount of carbon is low, less than 2.1 percent. If there is more carbon than this, it is referred to as cast iron, which is too hard to use for knives. The steel used in the construction of the knife may be a very important consideration, depending on the environment you live in. While there are many types of knife steels, there are three main types used for knives: carbon steel, stainless steel, and laminates.

Carbon steel: many knives produced today are made of carbon steel, and most custom made knives are also carbon. Carbon requires less processing than stainless steel and is more readily available to private knife makers in the forms of car springs, large saw blades, etc. Some common types of carbon steel include 1095, 5160, 1080, and A2.

Carbon steel knives are strong, keep an edge for a long time, and can be sharpened to a high degree (although these qualities also depend on the heat treatment used in making the knife). Some bushcrafters prefer a carbon steel knife as it can also be used to strike flint (the rock) for fire making.

The main drawback to carbon steel is its vulnerability to rust, and in coastal areas, rainforests, and areas with high humidity, a carbon steel knife must be constantly maintained and oiled to prevent rusting, which pits and corrodes the steel, weakening it and making it more likely to break. Even just a day without maintenance can lead to rusting of a carbon steel knife in wet conditions. Some manufacturers, such as Cold Steel, use a black coating to protect the metal, leaving only the edge bare.

Stainless Steel: A steel chromium alloy with approximately 10% to 18% chromium added to the steel. Almost all kitchen knives are made with stainless steel, as are knives designed for watery environments. One of the most popular knife makers among bushcrafters is Mora, who produce most of their knives in stainless steel. Although they are highly resistant to rust and corrosion, even stainless steel knives will begin to rust if left wet over an extended period of time.

Mora Companion, stainless steel version, one of the best values for a bushcraft knife at around $20.

When stainless steel first began to be used in mass production knives, the quality was not usually high and stainless steel got a bad reputation as a knife metal as it was too soft and dulled quickly. While there are still many poor quality stainless steel knives on the market, today there are also many high quality ones as well.

Some good quality stainless steels include 154CM, 12C27 (also known as Sandvik, commonly used in Mora knives), the 440 series, ATS-34, and Aus-8. The 420 series of stainless steel is said to be softer and of overall lower quality. It is commonly used in cheaper types of knifes.

If you live in a coastal area, a rainforest, or a region with high humidity, a stainless steel knife is a far better option than a carbon steel one.

Laminated Steel: Laminated steel knives usually consist of an inner layer of carbon steel sandwiched between two outer layers of stainless steel. This provides the strength and resiliency associated with carbon steel, combined with the rust resistant qualities of stainless steel. Laminated steel knives are generally more expensive than either carbon or stainless steel ones.

Wood processing kit: on top, a Cold Steel Pipehawk, in middle a Bahco Laplander folding saw, and on the bottom a Mora Forest Exclusive knife.

Rockwell Hardness Scale

Named after the engineer who invented it, the Rockwell scale measures a material’s hardness based on indentations that can be made on it using a specialized and calibrated device. There are different devices for testing different materials, each with their own letter designation. The Rockwell scale used for knives is C. Knife manufacturers often include the Rockwell scale measurement as part of their technical data, usually designated by RC or HRC (Hardness Rockwell cone). The standard RC scale for knives may vary from 56- 64, with 56 being softer and 64 being very hard.

A knife with a lower RC rating will be more durable but will need resharpening more often (or may even be difficult to get a good sharp edge on), whereas one with a higher RC rating will maintain its edge longer, but will be more easily chipped because it lacks flexibility and is therefore too brittle. Axes and other heavy chopping tools have a lower RC rating, as low as 45, because they need to be able to withstand the stress from continuous chopping that would break a hard steel.

A good range for both durability and edge retention for a wilderness knife is HRC 57-60.

Handle

Besides the tang, another important consideration is the handle material into which the tang is secured, and how it is secured. The handle should be comfortable to hold and use in various carving and cutting tasks. It’s a good idea to actually hold the knife and see how it feels, rather than just ordering it through the internet.

Some handle designs may seem fine at first but are not comfortable to use over an extended period of time, and this is something that may only be realized after you are able to use the knife. Many people re-handle production knives for this reason.

For bushcraft and carving techniques, it is recommended to get a knife that has no upper guard or jimping on the back of the blade (small grooves to aid in thumb retention). An upper guard interferes with some carving grips, and jimping is uncomfortable on your thumb if you do any amount of carving. Some people modify knives with upper guards by cutting them off. Guards are a more important consideration in fighting knives than in bushcraft or utility knives.

What the handle is made of can also affect its comfort as well as overall durability. There is a wide diversity in handle materials and construction. They can be divided into natural and synthetic materials.

Synthetic Materials

The most common types of handles are synthetic and include rubber, nylon, Kraton, Micarta, G10, and plastic. Synthetic handles may have the tang inserted into them or be used as scales. Kraton, Micarta, and G10 are among the most commonly used in medium to high value production knives, and are reportedly the most durable. The more rubberized handles are usually soft and grippy, and are both more comfortable as well as more secure when the knife is wet. They are not as durable as the harder synthetic materials, such as Micarta.

Ka-Bar Next Generation fighting-utility knife with a Kraton handle that is comfortable and grippy even when wet.

The advantage of synthetic handles is that they are impervious to water and will not rot or warp from prolonged wet conditions. Some synthetic handles, such as those made of rubber or plastic, can more easily melt when left near a fire. Micarta has a high heat resistance, and Micarta handles sometimes have bow drill sockets in them. Another type of synthetic handle are those with cord wrapped around the tang, most often paracord. While these are comfortable, they are not durable and are difficult to clean (food, blood, dirt, and sweat become embedded in the cord fibres).

Natural Materials

This includes wood, leather, antler, bone, and ivory. Wood handles are among the most common of natural materials, usually made of hardwood. Wood handles were also the most common type of handle until the 20th century, and many people prefer them to this day for comfort and durability. Knives with wood handles may have stick or narrowing tangs that are pinned or bolted on the butt, or form the scales on full tang knives. Some have shorter tangs that are fit inside the handle after drilling and filing it out (sometimes referred to as a push tang), while others are pieces of wood split in half, with the tang section carved out, and then all the pieces glued together.

Leather handles are usually made of leather pieces with holes cut and stacked onto a stick tang, glued and clamped, and then shaped and secured with a butt cap of some kind. Older knives, such as the 1960s version of the USAF survival knife, have this type of handle.

Another method of making a stacked handle is to use a combination of materials. Sami knife handles were traditionally made of stacked wood, bone, antler and/or ivory.

Wood, antler, and ivory are sometimes used as scales on full tang knives, being bolted or pinned in place. Sections of antler are also used with the tang inserted into the pithy core of the antler (another type of push tang).

Natural materials such as wood and leather must be maintained with occasional oiling and/or beeswax to preserve and protect against moisture.

Sheath

A final consideration when selecting a knife for wilderness or bushcraft use is the type of sheath it comes with. Like handles, sheaths are made from a variety of materials, both natural and synthetic. Some knife companies offer both options for a particular knife model. Again, if you live in a rainforest or coastal area, or an area with high humidity, it may be better to get a synthetic sheath that is impervious to wet conditions.

Most synthetic sheaths are made from hard nylon or plastic. Kydex is a commonly used acrylic and PVC material that can be heat formed to friction fit the knife in place, reducing the need for retaining straps. It is also resistant to water and UV rays. Most Mora knives come with a simple, lightweight plastic sheath.

Leather is often preferred by people as it is quiet and easily repaired in the field. Many people also make their own leather sheaths. The main disadvantage of leather is that in wet environments it can lose its shape, become loose, and eventually mold or rot. To prevent this it must be treated with waterproofing (such as Sno-Seal or beeswax).

If you don’t like the sheath that comes with a particular knife, it is fairly simple to make one yourself, using either leather or Kydex (both of which are available from Tandy Leathers). There are numerous instructional videos on the internet showing how to make a knife sheath.

Posted on September 18, 2014, in Gear Reviews, Warrior Fieldcraft and tagged bushcraft knife, Knife, knives, survival, wilderness knife. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Geronimo’s Bowie knife is on display at Ft.Sill. And a Mora can not do detail work as well as a small trapper.The tweenager knives are worthless for chopping or detail work.

WoW, great article! So much information with everything one needs to know. Thanks!

This is the greatest post. I want to recommend this valuable information what is really helpful for the all knife user.

Lots of very good information in a quick and consise manner. Just to be fair, I would like to point out that nearly all knives from all brands have broken at some point. The Spyderco Bushcraft shown here was a one off and Spyderco,of course, took care of this man despite the fact his was a factory second and came w/o warranty as well as immediately responded to concerns about the skeletonization by eliminating that first hole on future production.

As a knife nut and an owner of the Spyderco Bushcraft(their G10 version) I just don’t want people leaving here with the wrong idea about this knife or Spyderco as a whole. Like I said, all knives break but its how the maker deals with it that speaks volumes and Sal(Spyderco owner) is regarded as being one of the most humble and respected men in a field of many big egos. He participates in knife forums and takes his products to heart. This is a major reason that I am a huge fan of his company on top of the fact they build what,IMO, are the best over all production knives.

The Bushcraft UK is one of the best bushcraft knives period, at any price. I would pit mine against any custom built, its just that good. I honestly don’t know how they manage to produce such a complex organic handle shape with such perfect tolerances repeatedly. This thing is simply incredible with absolutely nothing to catch your nail where the scales meet the blade stock. Grinds are also perfectly symetrical. I am not the only one who thinks this, just look up the reviews.

I have read plenty of horror stories of big egos getting in the way of customer service and dealing with knife failures. Unfortunately, many of these high end companies have a serious God complex and admitting that they may have made a mistake is not possible. This is why I won’t buy from Buck, Bark River and Mad Dog, these guys have had their egos go to their head and think that their customers are wrong in many cases even mocking them on forums backed by their scary cult followers. Its disturbing.

Thank for share, this guide hope me to improve my knife blog

The best survival knife is the one you have with you, if your knife is a bowie and weighs 2 pound it will be back at camp when you need it

@anonymous the best survival knife is NOT just “the one you have with you”. that says NOTHING on what makes a good survival knife and in effect, says that even some cheap chinese knife you bought at the chemist is the best. WRONG! the best is the one that performs the most functions for its size, what’s comfortable for your budget, can be on you when you need it and (suggestively) follows the points outlined by mors kochanski.

That old spyderco of mine is still making the rounds a decade after it’s death. I don’t recall hearing about them eliminating the front hole in the newer bushcraft blades. I must have missed that one.