Mexico’s Zapatista rebels, 24 years on and defiant in mountain strongholds

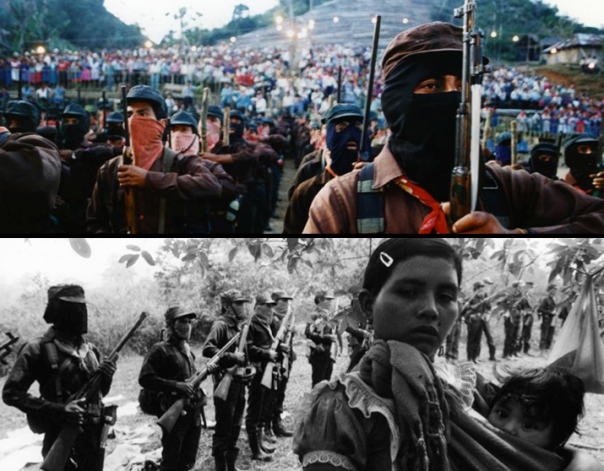

Members of the Zapatista national liberation army (EZLN) in La Garrucha, Chiapas, stand in front of a mural showing the revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata. Photograph: Eduardo Verdugo/AP

The peasant rebels took up arms in 1994, and now number 300,000 in centres with their own doctors, teachers and currency, but rarely answer questions – until now

Diners in the Tierradentro cafe in the southern Mexican town of San Cristóbal de las Casas can choose between a variety of omelettes. The “Liberty” has the most ingredients, the “Democracy” looks the best, but the “Justice” costs the most – possibly because it comes with cheese.

The restaurant is one of many celebrating, or cashing in on, the Zapatistas, the indigenous peasant rights movement from dirt-poor Chiapas state, which took up arms and occupied San Cristóbal on 1 January 1994, the day Mexico signed up to Nafta, the North American free trade agreement.

The rag-tag rebel Zapatista national liberation army (EZLN) – one-third women, some in bare feet, others with wooden guns – freed prisoners, burned military posts and seized ranches in protest at centuries of what they saw as oppression by large landowners and the government. They became instant heroes of the left, and an inspiration to indigenous groups and political romantics around the world.

Twenty-four years on from the rebellion, the restaurants in San Cristóbal thrive on their reputation, sporting mannequins in balaclavas, playing revolutionary music and selling T-shirts. Images of Che Guevara mix with those of Subcomandante Marcos, the poetic, pipe-smoking political philosopher who led the Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Ch’ol and Tojolabal peoples’ armed rebellion and who famously declared that the “fourth world war against neoliberalism and oblivion” had started.

“Zapatourismo is big,” says Manuel Heredia, a young Chamula Indian who was brought up in what is now a Zapatista community. “We have many American, British, Italian and others coming here. Every day sympathisers come to San Cristóbal. They want to know about 1994, and what happens now.”

Today the Zapatistas, who have never disarmed, claim to control much of the state of Chiapas. “There are 50,000 families, or nearly 300,000 people in 55 municipalities. Their rules of ‘good government’ involve giving their time several days a week to the community, sharing food, helping to teach the young, and organising,” says Heredia.

“They are autonomous,” he adds. “Most villages are in the mountains and the great Lacandon forest. They have their own system of education, health, justice, government and security. They are still poor but they train their own teachers and doctors, and some have their own currency. The Mexican government mostly leaves them alone.”

Top: Juan Popoca / Bottom: Ángeles Torrejón. EZLN guerrillas circa 1994.

There are no tour buses to Zapatista villages but visitors can ask in the Tierradentro cafe to go to one of the group’s five caracols, or administrative centres. The closest is Oventic, high in the mountains two hours from San Cristóbal. There, visitors are greeted by a sign saying: “Here, the people command and the government obeys.” and are warned that “Enrique, calling himself Geremia, is passing himself off as a Zapatista but is really an imposter”

Entry is by a gatehouse. A young man in a balaclava embroidered with a number 2 records names, nationalities and professions, and passes the information to an unseen reception committee, which decides whether to grant entry. It is not certain. After a long wait, a second masked guide arrives to take the Observer, a Mexican doctor and an Italian teacher round the settlement. The guide barely speaks Spanish. “No photographs. Only buildings,” he says.

The visit is short because it is the school holidays, and there’s not much to see. A few acres of land is being farmed for coffee and fruit, a secondary school for 150 children and a health centre have been built, a shop sells Zapatista music and embroideries, and there is a new hall with a stage and seats for at least 200 people. All the buildings have been painted with revolutionary art, many featuring snails, the symbol of the Zapatistas, and slogans like “Slow but safe” and “Long live the collective work of corn”.

Visitors are not charged and may not ask questions. But the Observer had been advised to submit six by email to the Zapatista leadership the previous night and, near the end of the tour, is invited into a small wooden house decorated with photographs of Che and the 1994 uprising.

Three masked Zapatistas sit, as in an interviewing panel, at a table, and four others perch on a bench beside them. They ask for names and identities.

“I will answer your questions all as one,” says their young spokeswoman, a masked Tzotzil woman, who will not give her name or say where she is from. “I am too young to know 1994 but the difference between then and now is that the older generation then did not know if we could even exist [as a people]. Today we have an identity.

“We were forgotten. Now we are known by everyone. In 1994, we had no hospitals or schools. Now we have them. Our work was hard. Now it is much better.”

She says the Zapatistas are unvanquished and happier, despite the Mexican government’s continuing hostility. “We do not need the government. We do not use them. We have our own indigenous government. We have different problems now, but we are finding the solutions ourselves. It is much better. There are many more of us, too. Our organisation is stronger. Things changed because we organised ourselves. We could not continue to live like we did.”

But while they reject globalisation, they are its beneficiaries, receiving aid from support groups in Britain, the US and across Europe. “Capitalism exploits and dominates. We are developing a new form of governance. The decisions [about how we live] are now made by the communities, not by government,” the young woman says.

She rejects suggestions that the Zapatistas have become a political cult that has turned its back on the outside world. “No. We are now self-reliant. We have email and the internet. We are part of a global indigenous movement. But our children don’t go to university. We teach ourselves. Our people work everywhere now, as teachers, farmers, communicators. We work with other Zapatistas and indigenous groups. The base of our society is people, not the capitalist system.

“Why do we wear masks? You must understand that we were the poorest people. We were marginalised. We still do not trust authorities. Even though we are autonomous now, there is still fear. We only wear our masks when we are with outsiders.”

“Their fear of exposure is sensible,” says Maria, a Tzotzil woman from the 5 March neighbourhood of San Cristóbal, where many urban Zapatista families squatted and settled after the 1994 uprising.

“The Mexican military seek confrontations. There are still arbitrary arrests, killings, harassment and violence. We are still poor. The big difference between now and then is the way women are treated. Women played a key role in the rebellion and are now the leaders. We are now equal. It has been a transformation in society.”

There are signs that the Zapatistas are ready to play a bigger part in wider Mexican politics. Although they have stated in the past that they want no part in state elections, they have an elected leader, María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, also known as “Marichuy”, who hopes to stand in the May presidential elections as the first indigenous woman candidate. She is not a Zapatista herself but there are 25 million indigenous people in Mexico, and many back her stand against deforestation, mining and the mega-projects that are devastating the country.

The Zapatistas are accused of splitting the traditional left vote but Comandanta Hortensia, one of their leaders, has responded forcefully. “The world is very big and all of us fit, all of us. The only thing that does not fit is the capitalist system because it dominates everything and doesn’t even let us breathe. Worst of all is that capitalism has no end – no death, destruction, misery or desolation is enough. No, it wants more: more war, more death, more destruction.”

Back in Oventic, the Zapatista spokeswoman sees the irony that they and President Trump, a despised figure, should find common ground in seeking to abandon the Nafta free trade agreement: “We knew that Nafta would lead to problems. But we didn’t know it would lead to him.”

Posted on February 19, 2018, in Uncategorized and tagged EZLN, Mexico, Mexico Indigenous, Zapatista Army of National Liberation, Zapatistas. Bookmark the permalink. 1 Comment.

Pingback: Viva EZLN! Ya Basta! Viva Revolucion! | ZONK